The past four hundred years have seen marked, absolute advances in American quality of life. Through means progressive (The Great Society) and destructive (The Civil War/The Trail of Tears), proactive (The Transcontinental Railroad) and reactive (The Marshall Plan), the American citizenry has grown through fits and starts to an overall improved state of well-being. (I maintain this truth while acknowledging that the human costs were, at times, appalling and reprehensible - not to mention avoidable; but that's not the focus of this entry.)

During this time period, our conception of poverty has also dramatically evolved through these general stages in the United States (at least according to those who could actually read and write and get published):

During this time period, our conception of poverty has also dramatically evolved through these general stages in the United States (at least according to those who could actually read and write and get published):

- Pre-Independence - Ignored

- Independence to the mid-20th Century - Explained Away

- Mid-20th Century to present - Considered & Addressed (by some, some of the time, in some ways)

Unfortunately, with dramatic advances have come horrifying side-effects and more recently, a frightening return to Gilded Age-style income inequality. Despite advances in absolute well-being and consciousness, tens of millions of Americans continue to live in poverty.

And yet, to the lay observer who believes this is a wrong and something should be done about it, the term “poverty” is actually of little practical use. Sure, the child poverty rate and other established rates are helpful statistics; but I am increasingly concerned that we as Americans are more comfortable shining a light on poverty without really knowing what we are talking about, which means it's also become a euphemism. If you look closely, you'll see that it’s an all-too-easily driven vehicle for the college educated to speak about a poorer, browner other - both domestically and abroad - and oversimplify the hopes, wants, and needs of anyone deemed as falling into that group. Intent and awareness aside, I believe we can agree that this is not a type of progress we want.

And though POVERTY!!!! is effective at grabbing attention, it's also a term that's tough to grab hold of and dissect. Is whoever brought it up talking about income? Dependence on government assistance? How persistent health problems can make it impossible to keep a job? Unemployment?

And yet, to the lay observer who believes this is a wrong and something should be done about it, the term “poverty” is actually of little practical use. Sure, the child poverty rate and other established rates are helpful statistics; but I am increasingly concerned that we as Americans are more comfortable shining a light on poverty without really knowing what we are talking about, which means it's also become a euphemism. If you look closely, you'll see that it’s an all-too-easily driven vehicle for the college educated to speak about a poorer, browner other - both domestically and abroad - and oversimplify the hopes, wants, and needs of anyone deemed as falling into that group. Intent and awareness aside, I believe we can agree that this is not a type of progress we want.

And though POVERTY!!!! is effective at grabbing attention, it's also a term that's tough to grab hold of and dissect. Is whoever brought it up talking about income? Dependence on government assistance? How persistent health problems can make it impossible to keep a job? Unemployment?

In short, I find its use to be limited, which brings me to the point of writing all of this. In the murky world of social impact, the problem must be specifically and clearly defined. It's the difference between saying "Wow, so many businesses have moved away since I was a kid," and "Median income in our county has dropped $3000 in the past fifteen years." And specificity about the problem at hand makes isolating causes and crafting solutions for individual communities a much more purposeful process.

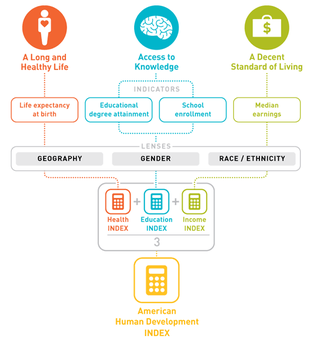

In an effort to better understand the broad state of things, I have found myself gravitating to the American Human Development Index. It considers three indicators - health, education, and economy. Life expectancy, educational attainment, and median income are the primary indicators, among numerous others. It's more specific than "poverty," which I appreciate, though it's worth mentioning that this is only statistical data; and anecdotal data is also needed. The upside, though, is that this lens for understanding quality of life makes it easier to seek out and clarify needs and narratives of individuals and groups in a way that an effort to "understand poverty" really doesn't.

In an effort to better understand the broad state of things, I have found myself gravitating to the American Human Development Index. It considers three indicators - health, education, and economy. Life expectancy, educational attainment, and median income are the primary indicators, among numerous others. It's more specific than "poverty," which I appreciate, though it's worth mentioning that this is only statistical data; and anecdotal data is also needed. The upside, though, is that this lens for understanding quality of life makes it easier to seek out and clarify needs and narratives of individuals and groups in a way that an effort to "understand poverty" really doesn't.

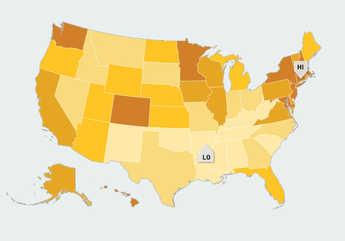

It should come as no surprise that this index is not kind to the South. Over the next twenty years, I believe that organizations seeking social impact that consciously match up data with narratives in the South to determine the way forward will bring about the most absolute good. I also believe that a fundamental piece of their strategy will be to focus their work around those human development indicators.

But that is simply a means to an end. My greatest hope is that the South becomes a place where progressive change is commonplace and ownership of that change is continually relinquished to those whom it is most likely to affect.

But that is simply a means to an end. My greatest hope is that the South becomes a place where progressive change is commonplace and ownership of that change is continually relinquished to those whom it is most likely to affect.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed